Engines of Light: The Race to Build the World’s Smallest Motors

Engineers built micromotors so tiny they trail the diameter of a human hair, powered by lasers rather than mechanical gears. Possible applications include medical tools at micro-scales.

HEALTHINNOVATIONSCIENCEFEATURED

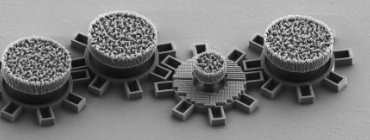

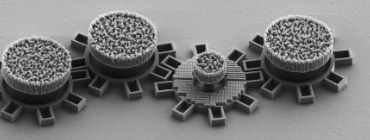

If you drop a grain of sand on your desk, squint at it, then imagine something a hundred times smaller — you’re starting to picture the scale of the latest breakthrough in micromachines. Scientists have developed micromotors smaller than the width of a human hair, powered not by gasoline, batteries, or even chemical fuel, but by beams of laser light.

To the naked eye, they are invisible specks. To engineers, they are tiny revolutions — literal ones, spinning with precision at microscopic scales. And to futurists, they are whispers of a coming age when medicine, environmental science, and manufacturing are powered not by machines we can see, but by armies of microscopic robots swarming through the hidden corners of our world.

A Century in the Making

The idea of shrinking machines to minuscule proportions isn’t new. In the 1950s, physicist Richard Feynman gave his now-legendary lecture “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” predicting a future where humans would manipulate and build at atomic scales. In the 1960s, science fiction writers imagined surgeons injected into patients aboard microscopic submarines.

But for decades, nanotechnology mostly meant theory. Motors — devices that convert energy into motion — proved particularly elusive. At the microscale, friction and inertia behave differently. Traditional gears jam, bearings seize, and lubricants fail. The very physics that makes engines hum in your car becomes useless when you shrink down to near-cellular size.

The breakthrough came not from mechanical tinkering, but from rethinking energy itself. Instead of fuel or electricity, why not light?

How It Works: Riding the Photon

The new micromotors are essentially tiny particles spun by focused laser beams. When photons strike these structures, their momentum transfers to the particles, generating torque. With the right shapes — think of microscopic paddles or spirals — lasers can make them spin at controllable speeds.

It’s elegant in its simplicity: no gears, no wires, no batteries. Just light and matter.

“The beauty is that light is abundant, controllable, and can penetrate biological tissues in certain forms,” explains Dr. Elena Rossi, a lead engineer on the project. “It means we can imagine motors that work inside living systems without bulky external power.”

What Can They Do?

At first glance, the micromotors’ abilities sound modest. They can stir tiny droplets of liquid. They can push other microscopic particles around. They can “swim” slowly through solutions.

But scale up the imagination, and the possibilities are staggering:

Medicine: Micromotors could deliver drugs directly to diseased cells, reducing side effects. Imagine chemotherapy targeted only to tumors, with motors carrying medicine precisely where it’s needed.

Surgery: Swarms of micromotors could one day clear blocked arteries or repair tissue damage from the inside.

Environmental Science: Released into polluted water, motors could break down toxins or carry out chemical reactions that clean ecosystems at a micro level.

Manufacturing: At the nanoscale, micromotors could assemble advanced materials, weaving structures too small and precise for human tools.

“Think of them as worker bees,” Rossi says. “Individually, they’re tiny. Together, they can transform entire systems.”

Quirks and Questions

Of course, there’s a whimsical side to the story. Engineers admit that early experiments looked like something out of a cartoon: scientists in lab coats firing lasers at flecks of dust, cheering as invisible motors spun for the first time.

And there are limits. The motors are delicate, and keeping them aligned with lasers isn’t trivial. Scaling up from lab demonstrations to real-world applications will take years — maybe decades.

There are also ethical questions. If swarms of invisible machines can clean rivers, could they also be misused? If they can deliver medicine, could they also deliver toxins? History suggests every technology carries dual potential.

Rossi acknowledges this with a smile. “We’re nowhere near sci-fi nanobot swarms taking over the world. But yes, as with all powerful tools, we need oversight and imagination in equal measure.”

The Quirky Side of Serious Science

What makes the micromotor story so charming is its blend of whimsy and weight. On one hand, it’s a tale of scientists making dust spin with lasers. On the other, it’s a possible foundation for medical revolutions.

That duality fits into a tradition of quirky breakthroughs — like the discovery of penicillin in a messy Petri dish or Velcro inspired by burrs stuck to a dog’s fur. Serious change often starts with odd curiosity.

“Science works best when we play,” Rossi says. “Sometimes, we’re just tinkering. And then suddenly, we’ve built the smallest motor in the world.”

Toward the Invisible Future

It’s easy to dismiss micromotors as too small to matter. But history shows that small things change the world. Transistors, once dismissed as “toys,” became the backbone of modern computing. DNA, just a molecule, unlocked the secrets of life.

Now, a new class of machines is joining that lineage. Engines of light, too small to see, powered by the hum of photons. They may not roar like car engines or spin like turbines, but in their quiet revolutions lies the possibility of reshaping medicine, environment, and industry.

And if nothing else, they prove that sometimes, the future starts not with thunder but with the tiniest of spins — a motor whirring invisibly, powered by nothing but light.